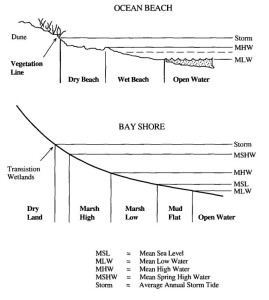

Figure 2. Ocean beach and bay shore tideland zonation (from Titus, 1998). Florida, Alabama, and Mississippi own up to the wet beach on the ocean. Louisiana claims up to the dry beach. Texas owns the wet beach, but maintains a rolling easement on the dry beach for public access. All states claim up to the mean high water mark on the bay side.

Both bay and ocean shores and tidelands are submerged lands claimed under the common law doctrines discussed below. Traditional sandy beaches come to mind when you hear the word “shore”. These beaches are part of the ocean or gulf side of tidal shorelines. However, they make up only 20% of our tidal shoreline. The rest of our shore occurs on the bay side: a mud-sand mix of vegetated marshes and open water that are critical support habitats for wildlife and fish (Titus, 1998).

Who Owns the Shoreline?

It is instructive to review where states claim ownership in tidal zonation because how that ownership is exercised impacts the ability to adapt to climate change, especially in terms of ability to armor the shorelines and thus impede inland migration of wetlands. Figure 2 shows the typical legal zonation along bay shores and ocean beaches found in most states. Ocean beaches for the most part are barrier islands and very sandy. The bay shores are the bay-side shores of the barrier islands and of the mainland.

In Texas, as in all the Gulf States, that portion of the beach seaward of the mean high tide line or mean high water (MHW) is owned by the state. Land lying above the MHW can be privately owned. In some cases, the vegetation line may be landward of the MHW. Some portions of the public beaches, therefore, are privately owned.

In all five of the Gulf states, a person needs a permit to build on submerged lands. There are significant differences, however, in how the states regulate submerged and adjacent lands, depending on whether these lands are on the bay side or the Gulf (ocean) side.

Gulf Side

On the Gulf side, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, and Texas own up to the wet beach (mean high tide line or MHW), but Louisiana claims both the wet and dry beach (to the vegetation line). Although Texas does not claim ownership of the dry beach, the state does expressly prohibit any construction or other impediments to access along the dry beach. No other state in the Gulf has a similar prohibition to protect access. Only Texas and Mississippi prohibit shoreline armoring or bulkheading on the Gulf shores or ocean side (although there is currently no development at all on the Mississippi barrier islands). Beach nourishment is permitted and occurs on the Gulf shores in all the states.

Bay Side

Things change quite dramatically on the bay side. Armoring, through the construction of bulkheads, the use of rock rip rap, etc., is permitted in all the Gulf states on the bay-side shores (inland from, but possibly impinging on, submerged land), but little or no beach nourishment occurs on the bay side in any of the states. (Titus, 2000). In all the Gulf states, shoreline armoring is much more common on the bay sides than on ocean shores for a variety of reasons (see Titus 2000, p.742): bulkheads are cheaper to construct on the naturally protected bays, there is much less demand for public access to the bay shores, and beach nourishment, which obviates the need for bulkheads, is not nearly as common as on the ocean beaches.

Rolling Easements: A Solution?

The result of this arrangement is that ocean side beaches generally have fewer bulkheads than bay-side shores and wetlands. Where shorelines are armored, inland migration of wetland will likely be impeded, hindering tidal wetland adaptation to climate change.

Shoreline armoring may be less common on ocean shores than bay shores in the Gulf states, but only in Texas is any construction on the ocean-side public beach outlawed. The way this law is set up and managed on the common law frameworks of the law of erosion and the public trust doctrine, is an important example of a legal framework that could enable the preservation of near shore inundatable lands for insuring wetland inland migration (transgression) associated with sea level rise.