Resiliency is an emerging concept in the world of urban hazard planning (Allenby and Fink, 2005). This concept is gaining meaning over the more widely used term “sustainability” because adaptive capacity to recover from disasters is a primary hallmark of long lasting, resilient coastal cities (Godschalk, 2003).

What is it that makes some cities more resilient than others in the face of catastrophes? Venice, through subsidence, is facing what many cities would face only under the worst-case scenarios for sea level rise. And yet in spite of serious problems, it is not yet collapsing into a different state. If anything, it is thriving. This kind of resilience is related, in part, to the strength of the urban infrastructure, and to the sturdiness of the structures.

What promotes Urban Resilience?

Godschalk (2003) and others cited in his paper point out that resiliency involves a balance of opposites: “redundancy and efficiency, diversity and interdependence, strength and flexibility, and planning and adaptability.”

- Urban forms which facilitate interaction and interconnectedness

- Land use regulations that keep people out of hazardous zones where possible

- Codes which promote more compact, yet sturdy buildings

- Strong social capital (Adger et al, 2005): the civic stock of public participation and public engagement that exist in a community — how well people can pull together in a crisis

- Preservation of natural areas for storm buffering

- Integrated local government authority, guided by strong federal and state mandates

Resilient cities as described by Godschalk have a “lifeline system of roads… and other support facilities . . . designed to continue functioning in the face of rising water [and] high winds . . ” Development is guided away from areas of known hazards. Buildings are constructed to codes designed for specific hazard threats. Natural areas are preserved for storm buffering as well as for other functions, and governments and other agencies have up-to-date information on hazards that they share through effective communication networks. In addition, there is a governance structure that gives local governments the maximum authority to create, under strong federal and state mandates requiring minimum standards, land use and hazard management plans best suited for their own conditions.

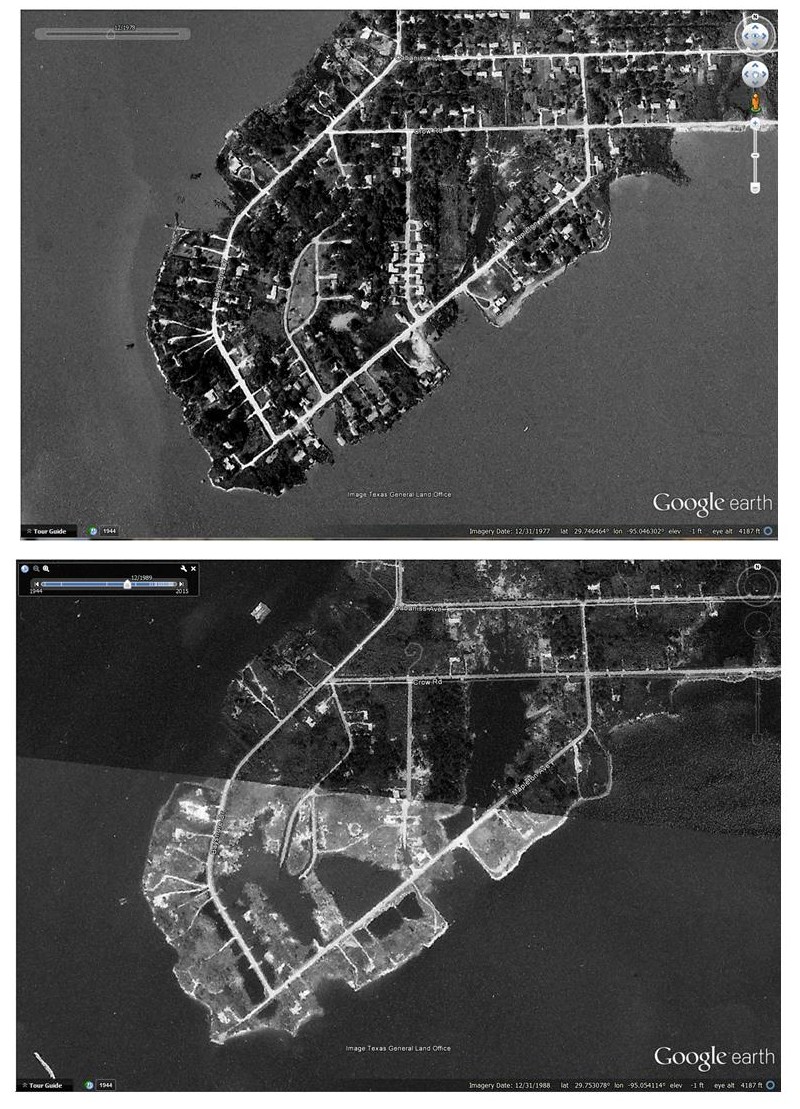

An example of a lack of resilience is the subdivision of Brownwood, in suburban Houston, which succumbed to subsidence and flooding, and was not protected, in spite of the considerable infrastructure in the neighborhood (Lockwood, 1996). Granted, there is no comparison with Venice, but the fact that Brownwood was so readily abandoned bespeaks a certain lack of community resilience. There really was nothing worth saving. There was no urban form that contributed to either social or infrastructural resiliency. There was nothing worth struggling for.