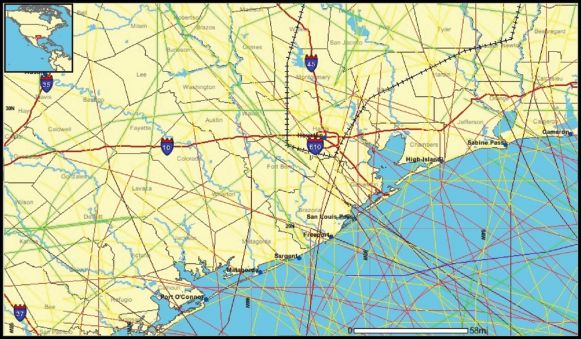

All Tropical storm and hurricane tracks for about the past 100 years of the Upper Texas Gulf Coast (taken from the Historical Hurricane Tracker: http://maps.csc.noaa.gov/hurricanes/viewer.html, NOAA Coastal Services Center). Storms increase in the intensity in the order green-yellow-red.

Planning ≠ Comprehensive Hazard Planning

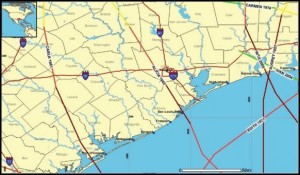

Plenty of planning is occurring in cities along the Gulf Coast. But the fact that plans have been made does not mean that effective, comprehensive plans which incorporate up-to-date disaster preparedness recommendations have been developed. Major tropical storms and hurricanes occur with such a relatively low frequency for any one place on the coast, that planners and engineers can easily become complacent about planning for future risks.

Same View as the figure above for past 50 years, Category 3 and above storms. This is the recurrence interval that might constitute the outer reaches of a communities’ “living memory”, and thus likely to have at least a marginal impact in planning horizons. While only Category 3 and above storms are shown here, it should be noted that lower category storms can sometimes have devastating consequences. Tropical storm Allison (2001), not even a hurricane, was the Houston area’s second costliest storm ever.

A Redevelopment Plan – do one before the disaster

Planning on the Gulf is an evolving process. Each major storm and disaster brings greater awareness of the need to plan for safer growth. In spite of a near-consensus in the academic planning community on the necessity of good comprehensive planning to reduce hazards, it is sobering to consider just how few municipal or county plans there are that effectively control development in hazardous areas (e.g., Catlin, 1997). In addition to the factors reviewed above, perhaps the greatest obstacle to effective planning is the fear of litigation related to government takings associated with limiting development.

Fortunetly, we know what it takes to plan effectively. Our review of some of the best plans in Florida revealed that the strongest planning language was often limited to indicating where hazardous areas occurred, with few limitations, except perhaps with respect to limiting density bonuses on development in these zones. Still, a simple portrayal of hazardous zones in a comprehensive plan has been shown to effectively limit densities to some degree in high hazard areas. And many plans in Florida and elsewhere do strongly tie building codes to hazard zones.

Very often the best opportunity to correct some of the mistakes from the past is after a disaster. But that is also the very worst time to try to plan for redevelopment, when recovery occupies all available energy and there is little available for strategic planning. Unless some good solid thinking has gone into how hazardous areas destroyed by a storm should be redeveloped, they will most likely redevelop as they were before they storm (Deyle 2010).